10 KiB

Testing With Two Computers

This is a simplified overview of conventional and coroutine-based unit testing. We explore the steps taken by a convnetional test and then present the same test in a coroutine model. We use an analogy with computers that can "only do one thing at a time" and then discuss how coroutines fit in at the end.

Conventional testing, using one computer

For this exercise, we will assume that the computers illustrated can only run a single "program" at a time. Therefore, whenever code calls a function, the computer is committed to running that function to completion before it can do anything else1.

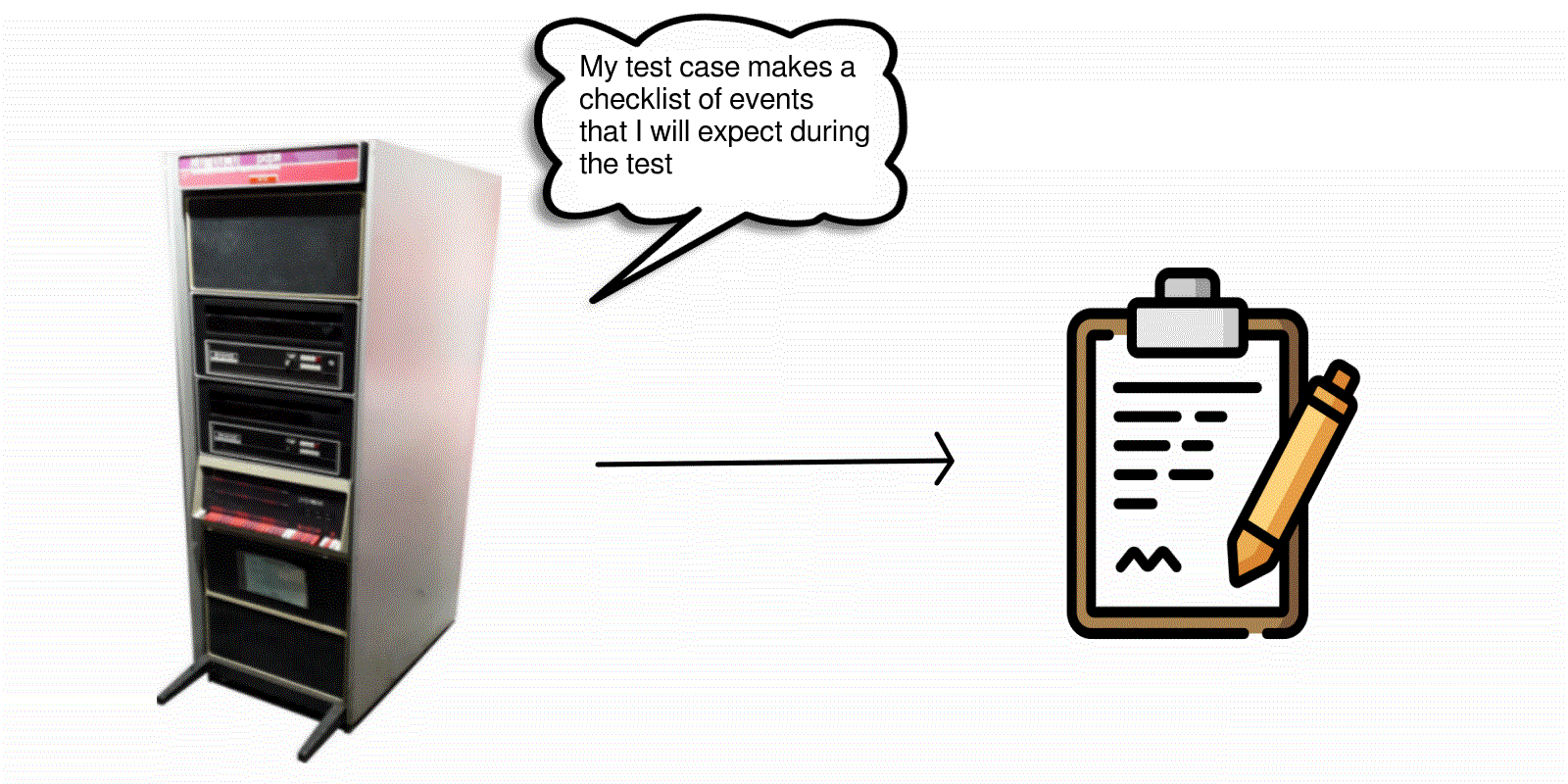

The computer is running a test case, which is a section of code written by a test engineer, against an API provided by a testing framework. To begin with, the test uses this API to fill in a kind of checklist (data structure) with information about what function calls should come out of the code-under-test.

Having filled in the checklist, we are now ready to begin the test proper. We use a coding practice called dependency injection to ensure that some or all of the outgoing function calls from the code-under-test actually come to us and not their original intended destination. There are a few different ways to do this, and the best option generally depends on the programming language in use. We implement this and call the code-under-test.

Having filled in the checklist, we are now ready to begin the test proper. We use a coding practice called dependency injection to ensure that some or all of the outgoing function calls from the code-under-test actually come to us and not their original intended destination. There are a few different ways to do this, and the best option generally depends on the programming language in use. We implement this and call the code-under-test.

The code-under-test has begun running on our computer. We must wait for it to either complete, or make a call that will come to us becuse of our dependency injection.

The code-under-test has begun running on our computer. We must wait for it to either complete, or make a call that will come to us becuse of our dependency injection.

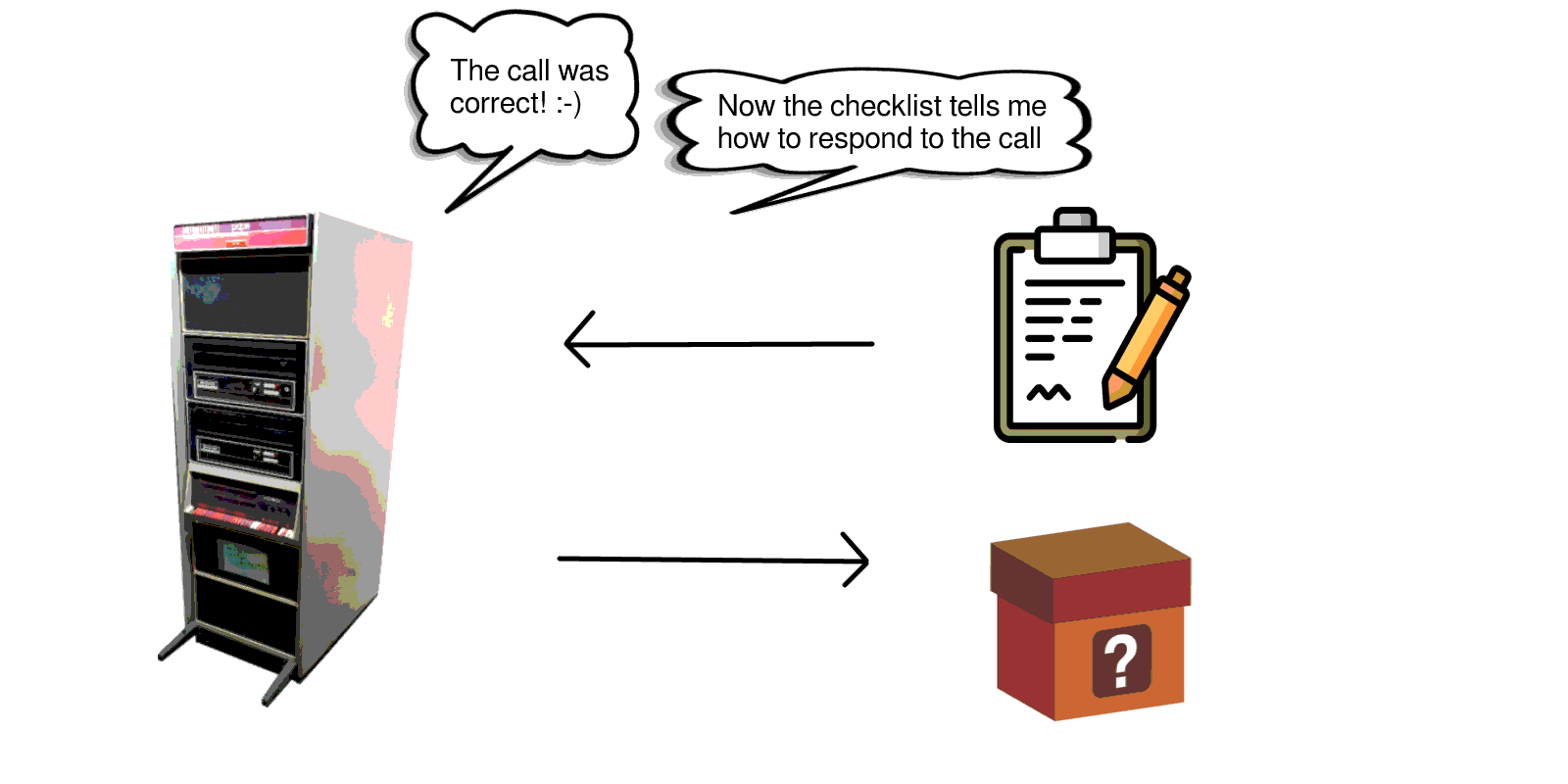

For the sake of example, let's assume a call comes to us. Because our computer is tied up with the call, it is not free to continue executing. Instead, it must handle the mock call in a specific place in the code, separate from where it called the code-under-test. Local variables will not be available, nor will the state-of-progress of any loops, if-statements etc. Therefore, it must use global variables to keep track of how far through the test it is. This is why a checklist is used: we keep track by "ticking off" items on the checklist as we receive the corresponding calls.

It is natural for the checklist to also contain an action to be taken and the required return value for the call. We can insert our own code here, but it is not freely running code: it needs to be put in the place alloted to it.

It is natural for the checklist to also contain an action to be taken and the required return value for the call. We can insert our own code here, but it is not freely running code: it needs to be put in the place alloted to it.

We will assume that the code-under-test now completes after making one call to us. The function call we made earlier on to start the code-under-test now returns, and we can check the return value using free-running code. We are also free to begin another test.

We will assume that the code-under-test now completes after making one call to us. The function call we made earlier on to start the code-under-test now returns, and we can check the return value using free-running code. We are also free to begin another test.

Alternative method

An alternative approach taken in the industry is to restrict the checklist to instructions on how to respond to calls. Then, while the copde-under-test is running we build up a record of what calls were made. This record is then checked at the end of the test by the test case. This method has advantages and disadvantages.

The same test, using two computers

For this exercise, we imagine that we have two computers similar to the one we began with, and that they have the ability to communicate. We will say that the first computer (shown on the left) has the responsibility of running the test case. The other computer, on the right, has the responsibility of running the code-under-test.

This time, there is no checklist to fill in, and so we proceed directly into the test. The computer running the test case will send a message to the one that runs the code-under-test, saying that it's time to start. Sending a message is a simple operation. Supposing a function call is made internally to achieve this - then that function returns either immediately, or as soon as any message is received in reply.

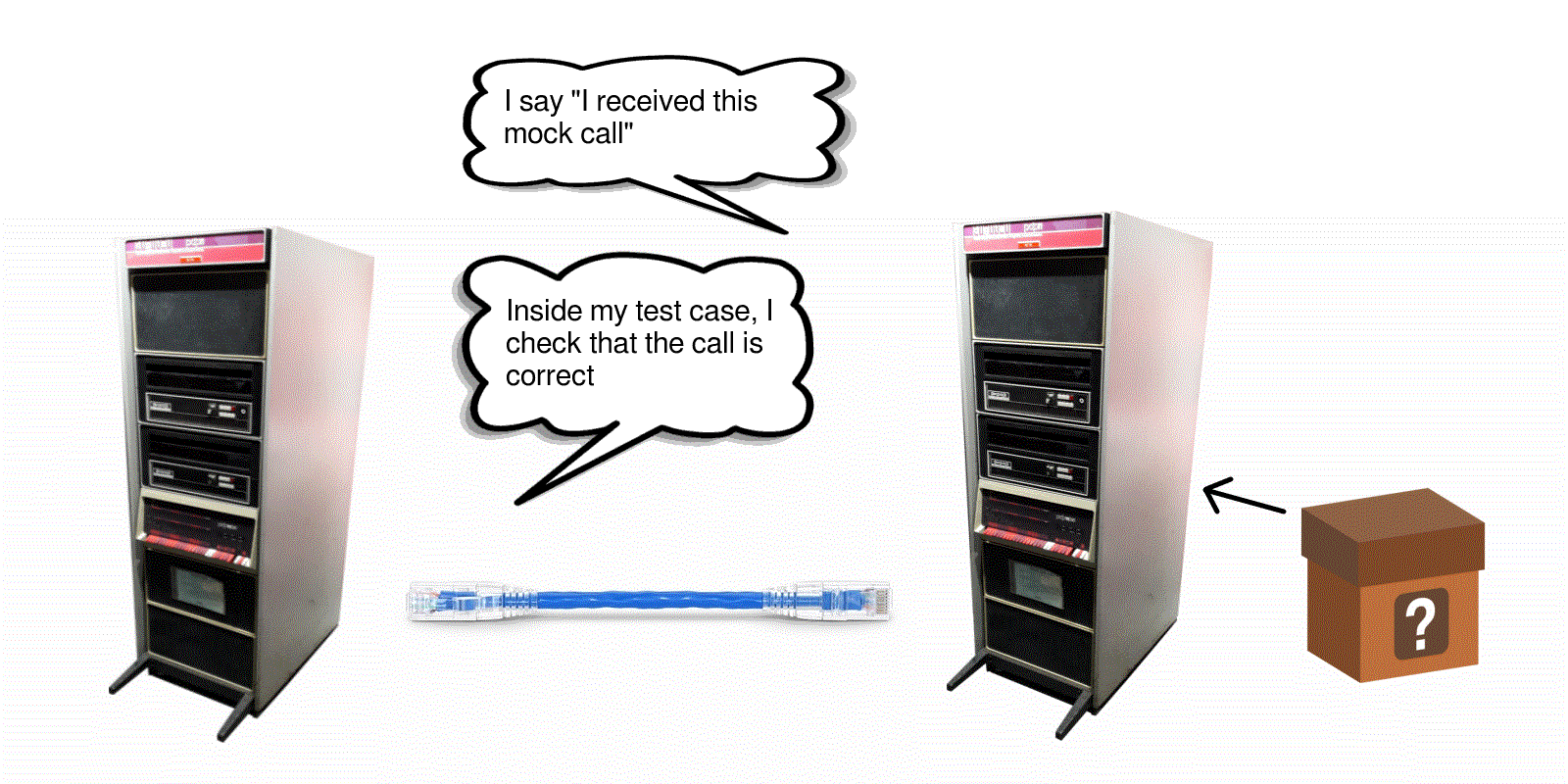

As before, we will assume that a call came from the code-under-test. The computer that runs it will generate a message for the testing computer with details of the call, and send the message. The testing computer is free to resume execution of its test case code. It accepts the message and immediately begins to check the call for correctness, much as we did at the end of the one-computer test.

As before, we will assume that a call came from the code-under-test. The computer that runs it will generate a message for the testing computer with details of the call, and send the message. The testing computer is free to resume execution of its test case code. It accepts the message and immediately begins to check the call for correctness, much as we did at the end of the one-computer test.

The reason the testing computer is free to do this, is because it is the other computer (the one that runs the code-under-test) which is tied up with a function call into that code.

The testing computer will proceed to perform any required action in free-running code, and then send a message to the other computer requesting that the call be returned, and including a return value if required.

The testing computer will proceed to perform any required action in free-running code, and then send a message to the other computer requesting that the call be returned, and including a return value if required.

Again the testing computer will be free to continue execution either immediately or when something happens (an event) that is important to it. We will assume that the code-under-test now completes, as before.

Again the testing computer will be free to continue execution either immediately or when something happens (an event) that is important to it. We will assume that the code-under-test now completes, as before.

Since the test computer is not waiting for the code-under-test to return, it must instead wait for the message from the other computer confirming that the code-under-test did return, and supplying any return value. It does not have to do this until it expects this to happen. It can now complete the test or start another.

Observation

We have been able to formulate the code constituting the test case as a sequence of message send/receive operations, interspersed with checking of received data and generation of new stimulus data.

We have not needed to build a checklist in advance of the test, nor (in the alternative model) verify a report at the end. Stimulus generation occurs just before use, and can take into account any event that occured previously during the test. Checking is done as soon as possible, so that failures can be identified soon after the presumed malfunction of the code-under-test. Segments of the test case could be placed in loops, for example, and the loop's progress will be preserved across incoming calls.

While the process of routing messages may require global variables, we no longer require them within the logic of the test case. The test case can itself be entirely contained within a single function, including the parts that deal with calls coming out of the code-under-test. Even in cases of highly complex tests (especially where the same outgoing function is called from multuple places within the code-under-test) we are usually able to avoid having to construct a state machine that programmatically maintains a correct answer to the question "where did we get to so far"; this information is now identified with the state of execution of the test coroutine. In other words, we have avoided the need for a meta-programmed test case.

How do we get to coroutines

It's obviously wasteful to require two computers. Can we do better?

First we should fix some terminology. When we have talked of computers and "programs", we really mean contexts of execution. It is a context of execution which is kept on-hold, or blocked by an outgoing function call, and must wait for it to return before it can continue to exceute in a natural way.

There are in fact plenty of ways to permit multiple contexts of execution in a single real computer. One would be to make explicit use of multiple cores (explicit binding), but this also seems wasteful. Without explicit binding, the main methods are processes, threads, and coroutines (sometimes called fibres).

Processes and threads differ in how memory is presented to the user's code. But both posess the interesting property that the computer's operating system can share CPU time across many of them, giving the impression that both are running at the same time (concurrancy).

However, in the above example it isn't necessary to do this. Where we have said, "that function returns either immediately, or as soon as any message is received in reply" it transpires that our objectives are fully met if the test case does have to wait for a reply. Indeed in a testing context, we might prefer to avoid the repeatability problems that can arise from cocurrancy, and so we might need to implement barriers if using threads or processes.

We are also interested in the speed with which we can pass these messages. Unit test code on modern hardware might be able to send up to about one hundred million messages per second and it would be unfortunate to reduce this significantly just because of a testing framework design decision.

This is where coroutines come in. These do not support concurrancy, and as a result can usually exist without the involvement of an operating system. With coroutines, it is natural to bind message-passing with switch of context of execution, so that both occur as a single event. This can require as little "a handful" of machine instructions. So we will plan to use coroutines as the implementation: everything will happen on a single thread and a single core, of a single computer. All that remains of the above exercise is the delineation of roles: there will be a coroutine that runs the test case, and another that runs the code-under-test.

-

The machine shown is a PDP-11/35 minicomputer system which does in fact support timesharing. You would not need two of them to run cotest! ↩︎